It’s hard to imagine this book being written in German but I guess it was,

by Herman Hesse as it is,

this is,

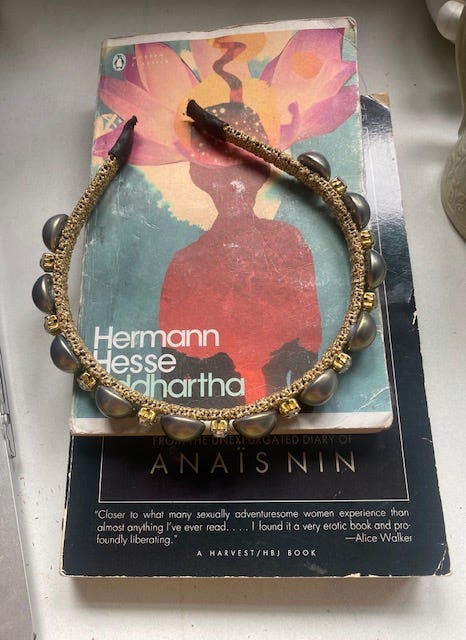

SIDDHARTHA.

Siddhartha by Herman Hesse

Score: 10/10

First published: 1922

Original language: German

And already young Siddhartha on the first page:

Already he knew how to pronounce Om silently—this word of words, to say it inwardly with the intake of breath, when breathing out with all his soul, his brow radiating the glow of pure spirit. (p.3) 1

This is the kind of book to bring to Church, to reach for in times of crisis, and to gift to the self-conscious shape-shifters… Siddhartha the hero, Siddhartha the popular boy—Siddhartha who doesn’t know who he is… but Siddhartha (unlike me) seems to think it’s something he can know:

One must find the source within one’s own self, one must possess it. (p.6)

So you can start reading Siddhartha as one man’s beautiful attempt to follow the well-known worldwide intonation:

KNOW THYSELF.

Who was it who first toned that? Plato? And was the bow of his head psychological or spiritual? Mine when approaching this question is always psychological, or social, but Siddhartha’s? Spiritual, definitely.

To whom else should one offer sacrifices, to whom else should one pay honour, but to Him, Atman, the Only One? And where was Atman to be found, where did He dwell, where did His eternal heart beat, if not within the Self, in the innermost, in the eternal which each person carried within him? But where was this Self, this innermost? It was not flesh and bone, it was not thought or consciousness. That was what the wise men taught. Where, then, was it? To press towards the Self, towards Atman—was there another way that was worth seeking? (p.5)

Atman, meaning breath, soul, essence in Sanskrit

Atman referring to the innermost part of our being

That bit through time which does not change

I don’t know if I believe in God or Atman but there is a time I come closest, when experiencing a feeling of reward after choosing to go down a certain path over others. It feels like I am rewarded as a consequence with good feeling. I can’t remember where it starts (maybe the heart?) but it definitely spreads across my chest. Strangely it is the only feeling in all my feelings that ever feels like it comes from above. I think Siddhartha might describe it here:

Siddhartha looked up and around him, a smile crept over his face, and a strong feeling of awakening from a long dream spread right through his being. (p.31)

This is what it means to to be strong,—or royal. To be royal you first have to have the power (the ability to make choices) and then you need the strength to make choices between choices AND follow them through. When Siddhartha feels the good feeling described above it’s because he has a realisation about his quest for Atman or Self which leads him to make a choice:

I will no longer try to escape from Siddhartha. I will no longer devote my thoughts to Atman and the sorrows of the world. I will no longer mutilate and destroy myself in order to find a secret behind the ruins. I will no longer study Yoga-Veda, Atharva-Veda, or asceticism, or any other teachings. I will learn from myself, be my own pupil; I will learn from myself the secret of Siddhartha. (p.31)

It’s this realisation in the novel which takes us onto the second part of the book—which is what makes me ask in life, what ever takes us onto a new part?

An epiphany, a realisation

And then (pivotally)

A decision.

For example, Siddhartha here:

Never to turn back.

PART TWO

When I’m reading this novel I get a little frustrated, frustrated I didn’t find it sooner… frustrated that even after I did find it I didn’t make a habit of reading it once every year. Of course, its wisdom wouldn’t have touched me any earlier—but now, here, reading this line at the age of twenty-seven:

To obey no other external command, only the voice, to be prepared—that was good, that was necessary. Nothing else was necessary. (p.39)

That’s so good for me. I remember many times I didn’t “listen to the voice”, adults don’t seem to take this intonation seriously without first having not listened to the voice and now showing scars… it seems mysterious to me, why didn’t I listen to the voice? Probably because I didn’t have a proper grasp of consequences at the time—that has to be one reason? That and I’ve always been seduced by the prospect of gaining new experiences... I am curious. Here I relate (heavily) to Anaïs Nin writing in her diary in Paris 1931:

The impetus to grow and live intensely is so powerful in me I cannot resist it. (p.1) 2

I am determined to have an experience when it comes my way. (p.2)

But now, from this dark room with dark textured walls, filled with seated booths and chairs which recline by remote controls (delighted beneath a weighted blanket) I say: I will listen to the voice. From now on I will listen to the voice and not only will I listen to it but I will listen out for it too. I will create spaces which are so quiet and still that it may have the chance of being heard because perhaps (and it should always be perhaps) if I know anything about myself it is that my voice is shy and tends to second-guess itself… but usually, in the first instance at least, my voice is right. A practical way for me to do this is to find 1-3 hours in the day to be alone, usually in the morning whilst drinking coffee (at home or in a café) to write… because it’s mostly-to-only when I write that I’m able to get in close proximity to the voice on demand. It’s like this passage (jumping in mid-sentence now):

[…] for to recognise clauses, it seemed to [Siddhartha], is to think, and through thought alone feelings become knowledge and are not lost, but become real and begin to mature. (p.30)

But if I change a few words it gets much closer to my reality:

For to recognise clauses in my diary, it seems to me, is to think, and through diarying alone my feelings become knowledge and are not lost, but become real and begin to mature.

So back to the simple command now, the famous intonation: “listen to the voice” (or as popularised by Star Wars “use the force Luke”) this is how it figures in Siddhartha (put here not so much for safe-keeping as easy access in the future):

Both thought and the senses were fine things, behind both of them lay hidden the last meaning; it was worth listening to them both, to play with both, neither to despise nor overrate either of them, but to listen intently to both voices. He would only strive after whatever the inward voice commanded him, not tarry anywhere but where the voice advised him. Why did Gotama once sit down beneath the bo tree in his greatest hour when he received enlightenment? He had heard a voice, a voice in his own heart which commanded him to seek rest under the tree… and he had listened to the voice. To obey no other external command, only the voice, to be prepared—that was good, that was necessary. Nothing else was necessary. (p.39)

This is my new project then: to listen to the voice.

Of course, it’s a double act because the first step is to listen to the voice and then you have to actually listen to the voice... I asked Una if she always listened to the voice and she said “yeh. Mostly” in her truthful offhand way. Then I asked her “why not always?” and she pulled a face, “sometimes it has really bad suggestions.”

What does the voice sound like?

If you’ve had a quiet contemplative life as fitting to the son of a Brahmin in 500 BC (like Siddhartha) it might speak to you in simple words… for example on page 41 when Siddhartha spots a young woman washing her clothes by the side of the river and he calls across to her to ask for directions they engage in friendly conversation until,

She placed her left foot on his right and made a gesture, such as a woman makes when she invites a man to that kind of enjoyment of love which the holy books call ‘ascending the tree'. Siddartha felt his blood kindle, and he recognised his dream again at that moment, he stooped a little towards the woman and kissed the brown tip of her breast. Looking up he saw her face smiling, full of desire, and her half-closed eyes pleading with longing. Siddhartha also felt a longing and the stir of sex in him but as he had never yet touched a woman, he hesitated a moment, although his hands were ready to seize her. At that moment he heard his inward voice and the voice said ‘No!’ Then all the magic disappeared from the young woman’s smiling face; he saw nothing but the ardent glance of a passionate young woman… (p.41)

In this example the voice is very clearly human. It speaks Siddhartha’s human language: “no”. But later on in life (perhaps after years of soft comforts and high pleasures) the voice becomes much more abstract… more of a bird song in your breast to which you have to turn an ear, listen closely? Maybe follow?

And this voice, under these new circumstances (untrained sparrow) might start to feel like an obligation to you. And you, you everyday scoundrel, might be too lazy to actually listen to the voice especially since it won’t promise glory or riches or fame. The voice is much more subtle than that. Life, is much more subtle than that.

P.S. the passage on love at the end of the novel might be a governing principle for the way I write?

‘And here is a doctrine at which you will laugh. It seems to me, Govinda, that love is the most important thing in the world. It may be important to great thinkers to examine the world, to explain and despise it. But I think it is only important to love the world, not to despise it, not for us to hate each other, but to be able to regard the world and ourselves and all beings with love, admiration and respect.’ (p.113)

This book should always be on my bookshelf.

Next.

Page numbers for Siddhartha from Siddhartha by Herman Hesse translated from the German by Hilda Rosner (London: Penguin, 2008)

Page numbers for Anaïs Nin from Henry & June by Anaïs Nin (Untied States of America: HBJ, 1989)